GENERALPLAN OST (GENERAL PLAN EAST)

THE NAZI REVOLUTION IN GERMAN FOREIGN

POLICY

WFF Documentary material on General Plan Ost can be read here.

Note: With the exception of the quotes from Mein Kampf, the translations of other quotations below have been provided by the World Future Fund staff.

In the nineteenth century the world experienced the most massive period of global imperialism since the time of the Mongol invasions of the thirteenth century. By 1900 four great empires had emerged: two giant land empires, America and Russia, and two giant overseas colonial empires, France and England.

Unfortunately, the scramble for world empire created the seeds of conflict, particularly since one major world power, Germany, had come late to the game of world empire and had ended up on the losing end of the global imperial power struggle. Other nations were also deeply embittered. China had been knocked out as a world power and was being torn to pieces by the European powers. Japan had survived but remained bitterly discontented with its share of world territory.

Imperial Germany's defeat in World War I compounded the sense of desperation in German geopolitical circles. Germany was stripped of the few colonies it had gained. The German fleet was sent to the bottom. The German army was so weakened that Germany could not even match the power of the Czech Army. (Click here to see a 1939 German view of Germany's position in the world as related to Britain and its Empire.)

It was within this context that Adolf Hitler began his bid for power. At the same time another figure in world geopolitics also sought power for Germany. This man was Karl Haushofer, one of Germany's leading geopolitical minds. Haushofer was a a highly ambitious man with a keen instinct for political intrigue. Through his friendship with Rudolf Hess, Hitler's deputy, Haushofer was able to bring his ideas to the attention of Hitler. At the same time, through his travels in Japan he also found a receptive audience among Japan's leaders.

Haushofer succeeded in convincing the leaders of Germany and Japan that both

nations faced doom unless they were able to create giant land empires to match

the four great world powers. Where would this land come from? There was only

one answer, the Soviet Union. The cornerstone of Nazi foreign policy was

the conquest of the European part of the Soviet Union, ideally in coordination

with a Japanese conquest of Siberia.

(The following map shows the world as it might have been if this plan had been

carried out.)

Writing in, Mein Kampf (My Struggle), in 1924, Hitler declared,

"We National Socialists consciously draw a line through the foreign policy trend of our pre-War period. We take up at the halting place of six hundred years ago. We terminate the endless German drive to the south and west of Europe, and turn our gaze toward the lands in the east. We finally terminate the colonial and trade policy of the pre-War period and proceed to the territorial policy of the future … if we talk about new soil and territory in Europe today, we can think primarily only of Russia and its vassal border states."[1]

AMERICAN IMPERIALISM AS MODEL FOR HITLER

Hitler's model for his

empire was America. He greatly admired America's policy of forced

deportations of local inhabitants and their replacements by European

immigrants. He sought to duplicate this concept on a far larger scale using far

more specific concepts of racial and eugenic thinking. Hitler sought

nothing less than a racial and demographic revolution in Europe, where

the racial and genetic structure of Europe's population would be rearranged

forever by means of a huge empire in the east where the "Aryan" blood of Europe

would expand its share of Europe's population.

As Hitler stated, "There [is] only one task, Germanization through the

infusion of Germans and to treat the original inhabitants like the Indians,"

meaning their forced removal.[2]

Hitler never significantly altered the global geopolitical vision that he outlined in Mein Kampf. Throughout the 1930s, in fact, Hitler and his representatives attempted numerous diplomatic maneuvers, before resorting to war, that were intended to give Germany a free hand in Eastern Europe. These maneuvers included attempts to form an agreement between Great Britain and Germany, in an effort to keep Britain out of a future German-Soviet conflict.

1937 Ribbentrop-Churchill Meeting in London

In 1937, for example, Winston Churchill held an extended conversation with Joachim vom Ribbentrop, who was Germany's ambassador to Britain at the time. Ribbentrop was remarkably frank during the discussion, explaining to Churchill that

"Germany sought the friendship of England ... Germany would stand guard for the British Empire in all its greatness and extent ... What was required was that Britain give Germany a free hand in the East of Europe. She must have her Lebensraum, or living-space, for her increasing population. Therefore, Poland and the Danzig Corridor must be absorbed. White Russia and the Ukraine were indispensable to the future life of the German Reich of more than seventy million souls. Nothing less would suffice. All that he asked of the British Commonwealth and Empire was not to interfere. There was a large map on the wall, and the Ambassador several times led me to it to illustrate his projects."[3]

Two years later, on the occasion of his birthday in April 1939, Hitler made similar comments at the Reich Chancellery in Berlin. According to one of his personal architects, Hermann Giesler, Hitler made the following comments:

"As always, everything comes down to [living] space' ... He (Hitler) did not want Germany's colonies any longer - at least not in the sense that one typically understands the idea: i.e., colonial possessions. ... [Hitler stated] 'Basically I am convinced that a people, as well as individuals, should not break the connection they have to the environment into which they were born. Foreigners, as well as some of our own alienated intelligentsia, mock the phrase 'blood and soil'. However, I find confirmation of this concept upon looking back into history, especially into ancient times. Only the connection of a people to its environment allows its living will to grow and the strength of its long-standing, multifaceted culture to become differentiated. (p.375) ... The German people belongs to continental Europe.'"

Adolf Hitler spoke further about the seizure of land in areas and on continents that was practically empty of people or were thinly settled, such as the areas of the present-day USA, of Canada, and of Australia. He then sketched out the brutal repression or extermination of the far inferior native inhabitants."[4]

1939 MEETING BETWEEN HITLER AND BURCKHARDT AT THE BERGHOF

(WFF has only English translation of

transcript of this on the web.)

Finally, only weeks before the outbreak of war, Hitler hosted Carl J. Burckhardt, the League of Nations High Commissioner for the Free City of Danzig, at his private retreat on the Obersalzberg. Hitler expressed his aims to Burckhardt in no uncertain terms:

"We need grain and timber. For the grain I need space in the east; for the timber I need a colony, only one [colony] ... Our harvests in 1938 and in this year were excellent. We can survive, in spite of the triumphant cries of others that we will starve ... However, one day the soil will have had enough ... What then? ... I do not harbor any romantic aims. I have no wish to rule. Above all I want nothing from the West; nothing today and nothing tomorrow. I desire nothing from the thickly settled regions of the world ... All of the notions that are ascribed to me by other people are inventions. However, I must have a free hand in the east. To repeat: it is a question of grain and timber, which I can find only outside of Europe."

"Everything I undertake is directed against Russia. If the West is too stupid and too blind to comprehend this I will be forced to reach an understanding with the Russians, turn and strike the West, and then after their defeat turn back against the Soviet Union with my collected strength. I need the Ukraine and with that no one can starve us out as they did in the last war." [5]

The conquest of Russia's economic and agricultural assets would create a global superpower that could become the number one state in the world. This idea was not a fairy tale. Had Britain remained neutral (as Hitler hoped) a joint German and Japanese invasion of Russia would almost certainly have succeeded. A map of Hitler's long term goals of conquest can be seen here.

IMPLEMENTING GENERAL PLAN OST

Soon after Germany conquered

Poland in September 1939, Hitler directed SS chief Heinrich Himmler to begin

distilling his geopolitical aims into a formal plan of action. The newly

conquered territories of Poland, and lands Germany intended to conquer in the

western Soviet Union, lands Himmler referred to as the "California of Europe,"

would be "Germanized."[6] In

1940, Himmler had experts in the Reich Office for the Strengthening of Germandom

(RKFDV) and the Reich Security Main Office (RSHA) develop plans for the

territory won by the Third Reich through its military conquests in Eastern

Europe. Known alternately by their names as the Generalplan Ost or the

Gesamtplan Ost (GPO), the different versions of these plans envisaged a

comprehensive restructuring of social, political, ethnic, and economic life in

occupied Bohemia and Moravia, Poland, the Baltic States, and regions of the

Soviet Union west of the Ural Mountains according to National Socialist

racial-political principles. The GPO was in effect a utopian, ideologically

oriented plan for the creation of a German land-based empire in the east. As

such, the Generalplan Ost represented the most detailed statement ever

produced during the Third Reich of long-term foreign policy goals that Adolf

Hitler had first articulated in the mid-1920s.

Following an anticipated victory over the USSR by Nazi Germany in 1941, the

SS (assisted by military and civilian authorities) intended to depopulate the

regions listed above through the use of mass deportations and the physical

liquidation of some parts of the indigenous population. Those who had been

uprooted would be forced across the Ural Mountains into western Siberia. Still

others would be disposed of using mass killing methods perfected by the SS

during the slaughter of European Jewry. For reasons that remain unclear, SS

planners included in the GPO provisions for the expulsion of all of Europe's

Jews from the German sphere of influence, even though the regime had begun

deliberately murdering Jews en masse in late summer 1941. The Slavs and

Jews expelled from the "new German East" would then be prevented from returning

west by the creation of a fortified borderland that stretched from the Arctic

Sea to Astrakhan in the Caucasus.

In their place, the SS intended to settle communities of millions German

warrior-farmers (Wehrbauern) from Germany, Holland, Norway, Denmark, and

other countries with Germanic-Nordic racial stock would settle in the lands

between the eastern frontier and the German homeland.

This picture from an official Nazi publication shows a German vision of its

geopolitical future in an eastern empire.

[1] Adolf Hitler, Mein Kampf 8th Edition (New York: Houghton Mifflin, 1939), pp. 950-951.

[2] Minutes of Hitler Conference, 17 October 1941 reproduced in Czesław Madajczyk, ed., Generalny Plan Wschodni: Zbiór dokumentów (Warszawa: Glówna Komisja Badania Zbrodni Hitlerowskich w Polsce, 1990).

[3] Winston S. Churchill, The Second World War: The Gathering Storm (Cambridge: The Riverside Press, 1948), pp. 222-223.

[4] Hermann Giesler, Ein Anderer Hitler: Bericht Seines Architekten Hermann Giesler (Leoni am Starnberger See: Druffel-Verlag, 1978), pp. 374-375.

[5] Carl J. Burckhardt, Meine Danziger Mission 1937-1939 (München: Verlag Georg D.W. Callwey, 1980), pp. 339-346.

[6] Himmler quoted in Ihor Kamenetsky, Secret Nazi Plans for Eastern Europe: A Study of Lebensraum Policies (New York: Bookman Associates, 1961), p. 191.

Documentary material on General Plan Ost can be read here.

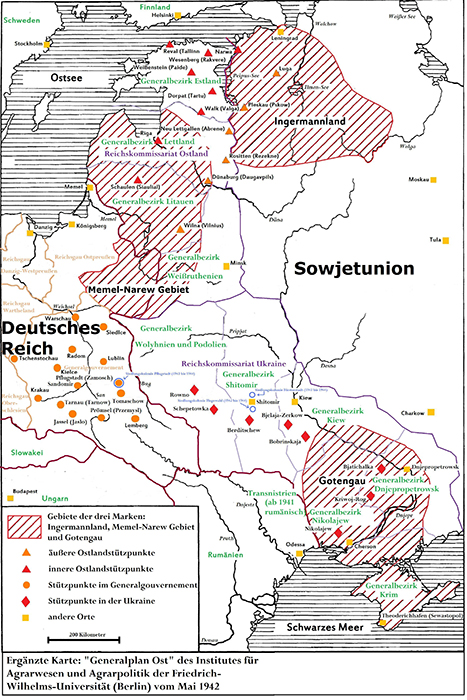

MAP OF GERMAN PLANS FOR SETTLEMENT